Why School Doesn’t Work the Way We Think It Does

- Greg Mullen

- Feb 10

- 8 min read

As debates intensify over charter schools, homeschooling, and “school choice”, one assumption remains largely unchallenged: that schools are neutral institutions whose primary job is to prepare students for participation in society. In practice, schools already model a particular version of society, one structured around competition, accumulation, and hierarchy, while presenting those outcomes as natural and merit-based.

However, many parents who are seeking schools that are fairer and more humane than the world their children will inherit may also expect schools to deliver the credentials and advantages required to succeed within that same world.

This tension sits at the heart of modern schooling but is rarely named.

Because this economic structure remains implicit, it is protected from scrutiny. What cannot be named cannot easily be reimagined.

A birdseye view of this structure at the state and district level shows schooling is unambiguously governed by currency. Tax revenues determine total capacity. Algorithmic funding formulas allocate resources based on attendance, demographics, compliance metrics, and categorical eligibility. Staffing, class sizes, intervention supports, enrichment opportunities, and disciplinary infrastructure all flow downstream from financial decisions made far above the classroom.

This economic logic does not stop at the schoolhouse door. It simply changes form.

Grades, Credits, and GPA as Academic Fiat Currency

Within schools, grades, GPA, and course credits function as a fiat academic currency, a system of value whose authority exists because institutions declare it to be so.

Like modern fiat money:

Grades are accumulated, stored, converted, and exchanged.

They grant access to advanced courses, extracurricular participation, rankings, scholarships, college admissions, and social status.

Their value is governed by rules set by leadership, not by any intrinsic or consistent relationship to learning itself.

This abstraction resembles the shift away from commodity-backed currency in the 20th century. Once detached from a tangible reference point, academic currency appears neutral, objective, and merit-based, even as its distribution remains structurally contingent on access to resources, support systems, and institutional fluency.

The result is an economy that feels moral rather than mechanical, earned rather than allocated.

Why the Absence of Physical Currency Matters

Because this academic economy lacks a tangible currency, its inequities are easier for many to deny. If schools issued literal paper notes tied to grades and credits:

The accumulation of advantage would be immediately visible in a microcosm.

The conversion of privilege into opportunity would be harder to moralize as “effort” distinct from effort by the less privileged.

The uneven impact of penalties and boundaries would be undeniable.

Without that physical representation, the system operates quietly:

Students with resources learn how to optimize accumulation of grade currency.

Most students comply just enough to remain stable with grades enough to keep them in extracurriculars or achieve a diploma by meeting minimum expectations.

Students with the fewest supports and most obstacles experience consequences without buffers, often being labeled as behavioral or motivational failures rather than economically constrained actors.

All of this is already happening, just without a ledger anyone is willing to name.

The Structural Deficiency Being Exposed

The core deficiency is not that schools fail to prepare students for “the real world.” It’s that schools simulate an economic hierarchy while denying it exists, a hierarchy that is born out of the same origins as our current individualistic capitalist society.

By keeping the currency implicit:

Inequality can be framed as individual failure.

Rule-breaking by the advantaged can be excused and normalized.

Rule-breaking by the disadvantaged can be criminalized or pathologized.

The moral language of schooling obscures what is fundamentally a resource-allocation system.

Why Shifting Toward a More Equitable Model Is So Difficult

Reimagining schooling in a more equitable way is not merely a technical or pedagogical challenge but a cultural one. School systems do not exist in isolation; they are embedded within communities whose adults have been shaped, rewarded, and stabilized by the very economic model schools implicitly reproduce.

For many parents and leaders, the existing structure of schooling feels familiar, legible, and earned. Grades, rankings, and competitive pathways mirror the society they navigated successfully (or at least learned to survive). As a result, efforts to change the rules of schooling are often experienced not as improvements, but as disruptions to the only social order that has ever felt real or reliable.

To alter the implicit economy of school is to quietly question the legitimacy of the broader system it reflects:

Schooling implicitly treats grades as moral signals, equating high academic performance with responsibility, discipline, and deservingness. If grades are not neutral measures of learning, then past academic success becomes less securely tied to moral virtue and more clearly shaped by context, support, and access.

The system assumes accumulation reflects fairness, suggesting that those who earn more grades, credits, and credentials have simply worked harder or made better choices. If accumulation is structurally advantaged, then fairness is no longer absolute—it becomes conditional on starting position and available resources.

Outcomes are commonly understood as natural and predictable, reinforcing the belief that existing hierarchies are the logical result of effort and ability. If different rules are possible, then current outcomes are revealed as produced by design rather than dictated by necessity (an uncomfortable revelation).

This creates a paradox.

School communities often hold two expectations of schools at the same time:

that schools should reflect a fairer and more humane ideal for their children that is not necessarily provided by existing society's social and economic order, and

that schools should reliably produce students who achieve “success” that mirrors the existing social and economic order, not excluding its inherent inequities.

This duality of expectations are rarely examined together, even though they pull in opposite directions.

As a result, communities ask schools to “prepare students for the real world,” while resisting reforms that would require schools to model the different or more humane version of that world. In this way, schooling tends to lean towards reproducing society as it is, rather than helping imagine what it could be.

Until this contradiction is acknowledged, attempts at equitable school models will continue to feel threatening, not because they are impractical or unsuccessful, but because they challenge deeply held assumptions about merit, success, and the legitimacy of the social order itself rooted in our current individualistic capitalist society.

The Bottom Line:

Schools don’t just "prepare students for the real world".

Schools prepare students for the version of society they determine is legitimate.

Extending the Argument: From School Structures to Household Structures

One implication of this analysis is that schools cannot meaningfully shift toward more equitable models in isolation. The contradiction schools are asked to navigate between modeling a fairer world and producing success within an unequal one exists just as powerfully within family households.

Homes, like schools, are structurally designed systems. They encode values through routines, incentives, boundaries, language, and definitions of success. Some households emphasize extrinsic rewards and compliance; others emphasize autonomy, negotiation, or collective responsibility. None of these designs are neutral. Each mirrors a particular interpretation of how we prefer society to run and how individuals are expected to function within it.

For example:

A household that ties chores, homework, and behavior to allowances or privileges reflects a model in which compliance is exchanged for reward, and motivation is externally managed through incentives and consequences.

A household that involves children in shared decision-making about responsibilities, schedules, and goals reflects a model in which agency, negotiation, and communal accountability are treated as skills to be developed over time.

When schools attempt to move toward more humane and equitable models, i.e. greater agency, transparency, shared accountability, or intrinsic motivation, they often encounter friction not because families disagree with those values, but because the structural logic of school begins to diverge from the structural logic of home.

The Problem Is Misalignment Without Translation

Importantly, alignment between school and home does not require uniformity. Families do not need to adopt identical practices, schedules, reward systems, or philosophies in order to support a shared educational ideal.

What they do need is:

A clear articulation of the values the school is trying to model

An explanation of how those values are expressed structurally (not morally)

Permission for families to pursue those same values in their own way

Without that translation, families often interpret school reforms through the lens of familiar systems:

Agency sounds like a lack of structure

Equity sounds like lowered expectations

Flexibility sounds like inconsistency

In reality, these reforms are often attempts to make structure more honest, not less present.

What Schools Can Offer Instead of Prescriptions: Self-Directed Schooling as a Cultural Design

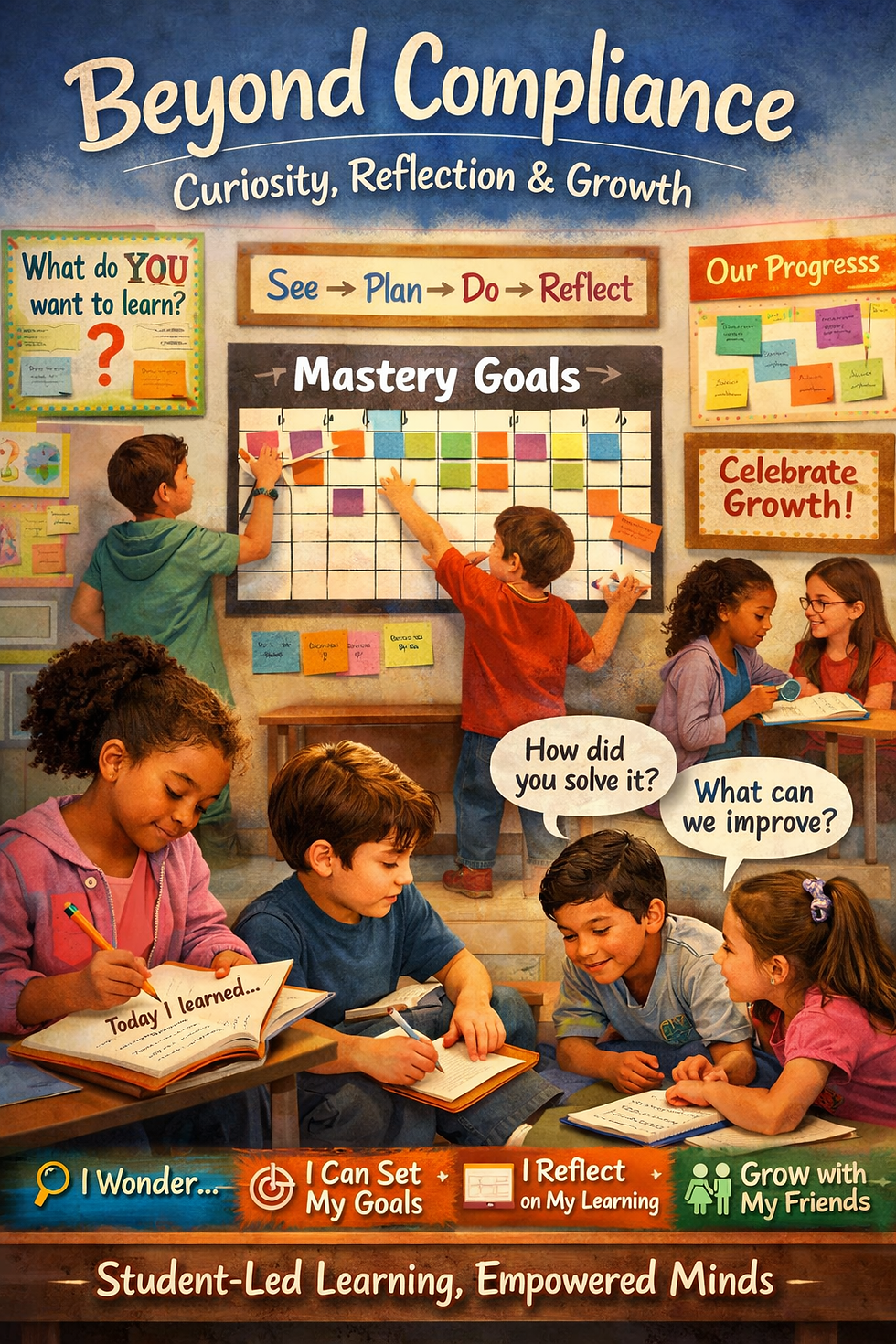

Self-Directed Schooling (SDS) is not simply a method, a schedule, or a set of classroom strategies. It is a cultural design for learning grounded in the belief that agency, responsibility, and meaningful participation are developed through experience, not enforced through compliance.

In contrast to traditional schooling models where structure is primarily imposed externally through grades, pacing, and behavioral control, SDS makes structure explicit, shared, and progressively internalized by students over time as developmentally appropriate.

At the cultural level, SDS is organized around a small set of core values:

Agency over compliance — students learn to make choices and understand their consequences

Responsibility through ownership — accountability is developed by participation, not fear of penalty

Transparency over hidden rules — expectations, goals, and systems are visible and discussable

Growth over accumulation — learning is measured by progress, reflection, and skill development, not currency alone

Community over competition — individual success is understood within a shared learning environment

These values shape how learning is structured, assessed, and communicated—not only to students, but to families.

Where Structure Lives in Self-Directed Schooling

A common misconception is that self-directed schooling removes structure. In reality, SDS relocates structure. Rather than concentrating control in grades, incentives, or adult authority, SDS distributes structure across:

Clear learning goals and skill progressions

Shared norms and agreements

Reflection tools that help students track effort, strategy, and growth

Gradual release of decision-making as students demonstrate readiness

This allows students to build system literacy—an understanding of how learning systems work and how to navigate them intentionally—rather than simply learning how to comply.

What SDS Offers Families Instead of Prescriptions

Because SDS operates at the level of culture and values, it does not require families to replicate school practices at home. Instead, schools practicing SDS can offer families clarity without control.

Rather than saying, “Motivate your child this way,” SDS-aligned schools communicate:

What values the school is intentionally cultivating

How those values are expressed structurally at school

How students are supported in developing agency and responsibility over time

Families are then free to pursue those same values in ways that fit their household structure, culture, and constraints. In this way, conversations between school and home are not prescriptive but rather mutually open to how best pursue those values specific to the needs of a particular student. A family might still use rewards, firm routines, or hierarchical decision-making and still support SDS because alignment is defined by shared direction, not identical methods.

To address the paradoxical nature of such contradictory school-home connections, rather than pretending schools are neutral or that society is already equitable, SDS:

Names the economic and social structures students are navigating

Teaches students how to operate within systems without reducing learning to accumulation

Models a more humane version of participation without denying the realities of the current world

The family of a student may insist the student achieve grade level academic expectations. The school can provide the resources and support for that student to achieve that goal. In this way, SDS allows schools to prepare students for society while providing the same set of values but with a different set of parameters for pursuing those values.

Ultimately, Self-Directed Schooling offers schools a way to articulate an ideal (i.e. agency, responsibility, transparency, and community) without imposing uniform expectations on all families. This does not ask homes to mirror schools. It asks schools to be honest about the culture they are cultivating. That honesty is what makes alignment possible without requiring sameness across homes.

Greg Mullen

Feb 10, 2026